REALJimBob

Fortysomething, photographer slacker, working in IT, living in Greenwich; failed polymath; drinks and eats too much, reads too little...

Women Destroy Everything

One of my hobbies is funding speculative fiction anthologies on Kickstarter. Usually, the ones that do daily updates annoy the fuck out of me. Lightspeed's current drive for a "Women Destroy Science Fiction" anthology is the rare exception, where I actually look forward to seeing new updates. I'm linking to one of the early ones, because YES, OH SO YES.

They've already more than met the goal for the original anthology and are closing in on destroying Horror as well.

Whether you are inclined to fund or not, you may enjoy perusing the updates. I know they turn my pupils into little black hearts.

1

1

Earth by Mur Lafferty

This feels like a transition story to be honest. Nothing much happens. Well, that's kinda unfair, lots of stuff happens I suppose, but nothing comes to any conclusion. Even in a series of stories like these, there has to be some conclusions in each story to make it a progression. Kate and Daniel are running Heaven and Hell respectively now they are gods. Kate seems to be having an easier time of it – at least her minions are being helpful and not trying to overthrow her. Daniel is struggling more. A lot more. But it's OK because Kate is cutting him pretty much zero slack (what did she ever see in him?). I can see the characters that Lafferty is trying to portray here: Kate is doing things the proper way and Daniel is a shortcut seeking corner cutter. Apparently when you're gods there is no excuse for shortcuts – at least in the opinion of the one having the easier time of things. It doesn't help Daniel's case that his shortcuts go drastically wrong, but it's not like he planned it that way.

At the end of the previous story the Earth was destroyed, causing a massive influx of souls to the heavens and hells. The missing Earth though is causing an imbalance in the universe and Kate and Daniel are charged with recreating the Earth ASAP. Recreating the Earth seems to also create three continents and a whole new religion. And this is where things start to get confusing. There's a new religion on Earth, plus all the gods in Kate's head, plus everybody else that they keep running into. The various heavens and hells appear to be running into each other. I was never sure quite how deliberate this confusion was. If it was something that Lafferty was going for as part of a transition from the first half of the story to the second; or if this was just the middle-story-confusion that often seems to hit otherwise excellent series?

1

1

Icebreaker (James Bond 3)

So, I relented and gave Gardner another chance. After the frankly disturbing end to the previous Bond novel, For Special Services, I was tempted to walk away but for pennies plus postage for an almost-new copy of Icebreaker at least I'm not really bumping his sales directly. The Gardner run has to end eventually (he did write 14 of these things) and another (read: hopefully better) author will take the reins – or maybe he's improving with time?

And, maybe, just maybe he is ... It starts with a good start, some solid functional scene setting and then straight into the action. Bond finds himself drawn into the ongoing operation Icebreaker. Given very little briefing by M he's on the Finnish/Russian border with a Russian, an American and an Israeli. It starts to sound like the beginning of a joke, but the jokes come later once Gardner gets going – really the idea of small group of Finnish Nazis rising again to try and take on the world seems laughable – although at least there's no goose-stepping. The number of double-crosses and double-double-crosses is insane, and while it's not overly confusing you do soon start to assume that everybody is going to change sides at least once during the book. The language is typically wooden, jumping between dialogue and third-person mid conversation, in a way that just feels stupidly clumsy.

But while it's far from a great book, it's not a bad Gardner Bond. There are definite signs of improvement here. I feel like we've turned an important corner. Most of the misogyny appears to have gone, although again Gardner seems to spoil that win somewhat by making Bond suddenly some kind of male incompetent, unable to decide which woman he loves/trusts implicitly or which woman he no longer loves/trusts implicitly. He completely loses any ability to form objective judgements of those he's working with – especially the various women – gone is the decisive Bond who trusts no one and instead he can't even be bothered to order simple background checks preferring instead to "uhm" and "ahh" his way through each character assessment. In fact, Bond appears to be the only spy in the game who isn't living up to his mistrust quota. The others seem to be acting out some pulp Mafia story rather than pretending to be professional spys. At the first opportunity Bond is over-sharing with the wrong woman when he should be getting his mistrustful spy on instead.

2

2

Changeless by Gail Carriger

A return to the bizarre paranormal-steampunk-romance-comedy-of-manners in the sequel to Soulless. This time, sadly, there doesn't appear to be any treacle tarts. Gingersnaps get a couple of mentions, but to be frank they aren't treacle tarts, and more's the pity. More books need treacle tart in them (so to speak). Alexia Tarabotti is now Lady Alexia Maccon, having married Lord Conall Maccon, the Earl of Woolsey and werewolf alpha. So, not only is she the only soulless preternatural in London and the muhjah to the Queen, she is now also Lady Woolsey and female alpha to the Lord's pack as well. They all live together at the pack's estate just north of Barking – Barking, geddit?

Suddenly a plague falls upon the supernatural set of London as they are all returned to mortal form. For vampires and werewolfs that means no shape changing, no super-human powers and no sleeping during the day. For the ghosts it just means they stop existing. As the only soulless in London, suspicion quickly falls on Alexia. Her touch returns supernaturals to their mortality, but never on this scale and never without physical contact. As her husband is called away to deal with a problem with his old Scottish pack, Alexia is charged to investigate by the Queen.

The world building and concepts are all as well thought out and presented as in the previous story. The addition of the avant-garde scientist Madamme Lafoux is enjoyable, with her Q branch like parasol of tricks, strange dress and possible links to the underground scientists. And the hot-and-cold relationships of Ivy Hisselpenny are amusingly intertwined with the main story. But the story is not without flaws – putting the lack of treacle tarts to one side, Madamme Lafoux's attraction to Alexia is so clearly telegraphed that it seems incredible that an otherwise smart woman could have made it through most of the book without realising. And, secondly, that the problems with the curse of mortality could have solved within a couple of chapters if only Alexia and Conall could manage to have a normal relationship where they talked about their obviously common investigations, rather than just arguing and shagging all the time. Instead we have to drag the investigation all over the country – even to Scotland of all places – before it can be solved. The big cliffhanger at the end – obviously a tease for the final book of the trilogy – didn't annoy me as much as it has some other reviewers: it's a series, you're always going to keep reading if you've got this far. Unless you don't like the book. But the cliff hanger twist seems like a natural device.

2

2

The Stainless Steel Rat Saves the World

Slippery Jim diGriz is getting told off by his boss, Inskipp, for stealing while on a previous mission for the Special Corps. Although, staffing a secret inter-galactic space police force with hardened ex-criminals is never going to be plain sailing I'd have thought. While he's being told off two things happen – firstly Jim surreptitiously helps himself to a number of Inskipp's expensive cigars, and secondly Inskipp suddenly disappears. He isn't the first either, a number of people are disappearing from Special Corps headquarters. In true Back to the Future style, somebody is changing the past (present) and causing people to disappear from the present (future). Luckily, there are just enough people left to fire up the time machine, that we didn't know about in any of the previous novels, and fling Slippery Jim, the Stainless Steel Rat, into the past to fight He and return time to its normal course.

What we have here is a Time War. Instead of Time Lords and Daleks it's between Slippery Jim diGriz, and his family and friends, and He, and his nefarious forces. The "He" name gets a little cliched at times. Both our hero and He himself seem to adopt the name without any real agreement. But, it does give Harrison an excuse to play games with He as a name and a pronoun in various forms. It did feel like he was still enjoying it more than me by the end of the book though.

The ending gets a little silly, with lots of people crossing lots of time-lines and creating all sorts of paradoxes left, right and centre. But it's important to remember that this isn't supposed to be a serious work of science-fiction where the time paradoxes are resolved in a way that actually makes sense. Instead this is supposed to be a humorous boys-own adventure, a bill it more than lives up to. Most of the humour is provided as Slippery Jim tries to adjust to life in the 'past' of 1975 on the strange planet of Dirt, or Earth, or whatever it's called (another joke that Harrison doesn't tire of). His attempts to describe everyday things, like TV adverts, are all the usual fun of the 'traveller out of time' trope.

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes

Another collection of Sherlock Holmes short stories, this time packaged as the memoirs of rather than the adventures of, but the format is the same: eleven stories from the archives of Dr. Watson. Some are from Holmes's early days, some from when Holmes and Watson were besties and some from after Watson had married and moved out. There are some innovations too however.

Firstly, we find out in The Greek Interpreter, that Holmes has a brother – Mycroft – who turns out to be much more corpulent than the TV representations had ever suggested. And, secondly, we find out that Holmes has an arch-nemesis – Moriaty – a criminal mastermind who suddenly appears out of nowhere in the final story, suitably titled The Final Problem. As with Irene Adler in the previous collection, these appearances seem a little sudden and a little short-lived compared with the frequent TV adaptations. One story in a collection of short stories certainly seems like much less than is deserved for the man who is not only the evil equal of Holmes, but as we probably already know manages to kill him at the end of only his first appearance. Feeling more like an unsatisfying postscript to the career of Holmes, The Final Problem, is disappointing and frustrating. Leading, as it did to the 8 year 'Great Hiatus'.

All the stories (unsatisfying endings aside) are good solid Holmes fare. Although Doyle does seem to be over-relying on the idea of the changed identity: the character who we think is one thing turns out to be somebody else. I generally found myself on the right track with solving the cases as Holmes does, but that certainly didn't spoil them for me. The charm of the stories is as much, if not more, in the characters of Holmes and Watson as it is in the complexity of the crimes and puzzles.

The two other stories that stuck with me ‒ although not necessarily for the right reasons – were The Yellow Face where we witness some very unsettling racism against the child of a mixed-race marriage where the child is made to wear a mask; and Silver Blaze which is effectively subtitled by Holmes as "the curious incident of the dog in the night-time" – an interesting nod, presumably made back to the story from Mark Haddon's own novel of that title.

1

1

Margaret Atwood – Oryx and Crake

A birthday present in 2012, it's taken me a while to get around to reading this. I've been enjoying the Atwood Positron series of short stories instead and figured I'd leave this one on the shelf for a while, but eventually all books must come down off the shelf and be read. Seeing the third book in this trilogy, MaddAdam, in the books shops convinced me to try and see if I could handle two Atwood series at a time.

Reading Oryx and Crake straight after Ballard's The Drowned World was a slightly disorienting experience: both are powerful human disaster dystopias; both feature narrator's whose mental health makes them slightly less than reliable; and both have quite limited casts otherwise. While The Drowned World was an environmental disaster, a lagoon in a flooded London; Oryx and Crake's is a biological disaster, an engineered virus wipes out the majority of the population, leaving a solitary human – Snowman, our narrator – and a group of engineered hybrid-humans who have been designed with immunity built in. The back-story and world building is provided through a series of flashbacks throughout the story, explaining how everybody came to be who they are and what happened to Oryx and Crake, as well as the rest of us. Obviously, this is Atwood, so the detail is excellently thought out. We understand the progression from nowish, through the rise of the biotech companies, the gated communities, the employer controlling the social existence of the employees; to the whole thing falling apart and the world, as we'd know it, ending.

Snowman narrates both the present time and the flashbacks, and his narration is built around his relationship with the hybrid-humans and we can clearly see that he lies to them as a matter of course. He's built an entire mythology around their origins. Every time they approach him to ask him a question about something he layers more on to that mythology. Oryx and Crake are the gods he has created to satisfy their curiosity. Crake was their creator, a genetic scientist and friend of Snowman, but now he's gone Snowman has built him up to be their god with himself as the intermediary, or prophet. Oryx has become the goddess of the animals in his mythology, rather than her previous role which was the original intermediary between Crake and his hybrid-humans before the viral disaster.

The nature of the novel feels slightly awkward having already read Atwood's In Other Worlds: it's a science based dystopia, it's set in the future, and it's fiction. In fact, the overreaching of science is pretty much the entire premise for the novel. But we all know that Atwood is a bit snooty about the term science-fiction and instead favours the term speculative fiction. Ultimately, it doesn't matter either way. It's not quite perfect, maybe a little too long, but Atwood remains the queen of speculative (or science-fiction) dystopias.

3

3

How Green This Land, How Blue This Sea

Zombies in Australia clearly means zombie kangaroos and wombats, silly accents and heavy on the cultural stereotypes. An American writing about a Brit in Australia always risks annoying any reader who fits into either category. Mahir is the Brit, visiting two new Australian journalists at End Times who think that the great Australian rabbit-proof fence would make a great story, and yes, as a fellow Brit he's starting to grate (I'll leave the Australian readers to moan about the Australian stuff). It's not just that he's sounding a lot less English each story, but he insists on narrating with American spellings, and I have never heard a Brit refer to sausages as links.

But to be honest, the cultural annoyances and Grant's check-list like need to have a non-heteronormative relationship appear in each book – incest, lesbians and now a polyamorous relationship – aren't really the problem. It's starting to feel like Grant is turning these out for the wrong reasons. Whether it's the cool idea (Zombie Kangaroos!) without a story, or just overwhelming pressure from publishers and fans to keep the universe going, the short stories are seeming to fall short of the original novels. Rather than developing the vestigial thriller that she teases, Grant spends way too much time getting over excited about the zombie kangaroos and talking in great detail about the rabbit-proof fence.

Set after the events of the trilogy, there are a few spoiler references littered throughout. Luckily, I wouldn't really recommend this for anybody other than completists anyway. With Grant branching out into her new Parasite series, maybe this is the end of the road for her Newsflesh series. This feels like the time to walk away before she really is just turning them out for the money, or possibly consider opening the universe up for other authors or fanfic.

Euan Semple was the guest speaker at our (not exactly) annual work conference, earlier this year, where he gave an excellent talk about his experiences with social computing at the BBC. Semple was the guy who introduced social computing to the BBC – initially mostly under the radar – consequently he's one of the best placed people to talk about the potential benefits to both companies and employees of embracing social computing (and more open knowledge management practices in general). At the end of his talk he, quite sensibly, had a little plug for his book: Organisations Don't Tweet, People Do.

The book is a series of 44 'thought essays' rather than a single work as such. Each essay is a variation on a number of themes. That companies, managers and employees shouldn't be scared of social computing; shouldn't fear the loss of control. That blogging, tweeting, just the act of writing down your thoughts provides both valuable business benefits and valuable personal benefits – as a form of self-expression, increasing your worth in both your current role and the next, forcing you to think about your actions and helping you to understand, and even shape, the world around you. That openness and honesty in your writing are the key to both success in social computing and not making (or recovering from) mistakes. That conversations between real people are more important than marketing and 'knowledge management'. That you can't easily have a strategy for something like social computing as it's still developing and changing too fast. And, that sometimes the inanity of the online can help cement the relationships. There is a subtext running through the book as well – many of these essays hint that they are also talking about changing the way you run the business in a social computing world rather than just how your current business should 'do' social computing.

Each essay is short, generally less than half-a-dozen pages each, engaging and well written; easily read during a visit to the executive bathroom (he says 'restroom' in the introduction, but I refuse). Unfortunately, while they are short, 44 is a lot of essays for a book on such a narrow topic. Many of the essays feel like different riffs on the same themes as previous ones. In part, maybe that's not such a bad thing: if we haven't grasped Euan's message yet, maybe he needs to repeat himself. But, as a reasonably seasoned Internetphile, I didn't feel I was getting as much out of the repetition as I had hoped. For somebody who is less experienced, or less convinced, about the benefits of social computing in a work context, it's probably a much more useful collection of writings and, hopefully, might change some hearts and minds.

1

1

An impassioned plea for Goodreads to stop the madness. To stop arbitrarily deleting 'reviews' just because they aren't simple book reports. To stop changing the rules of reviewing without actually telling Goodreads members. To stop refusing to explain, discuss, or entertain the possibility that they might have messed up a bit here.

What started as a "complicated prank" has become a collection of essays, deleted reviews, parody reviews, personal stories and saddest of all goodbye letters. Exposing and discussing the censorship, the inconsistency and even trying to drill down into some of the data to see if there are any patterns (spoiler: there doesn't seem to be). The ebook is available from Lulu for the cost of production only, also some contributing authors have posted free to download links for the book. Download and read – it won't take that long.

I have voted for this book as a write-in vote for the Goodreads Choice Awards 2013 in both the Non-Fiction and Début Goodreads Author categories. Apparently Goodreads uses the average rating of the book to 'weigh' the validity of write-in votes (presumably as part of their decision to censor those votes - but I digress) so I've also rated the book five stars. I encourage others to do the same (even if you feel the need to re-rate the book after the awards have closed).

I leave the final word to the (former) owner of Goodreads:

"I hope you’ll appreciate that if we just start deleting ratings whenever we feel like it, that we’ve gone down a censorship road that doesn’t take us to a good place." — Otis Y. Chandler, Goodreads CEO

4

4

An impassioned plea for Goodreads to stop the madness. To stop arbitrarily deleting 'reviews' just because they aren't simple book reports. To stop changing the rules of reviewing without actually telling Goodreads members. To stop refusing to explain, discuss, or entertain the possibility that they might have messed up a bit here.

What started as a "complicated prank" has become a collection of essays, deleted reviews, parody reviews, personal stories and saddest of all goodbye letters. Exposing and discussing the censorship, the inconsistency and even trying to drill down into some of the data to see if there are any patterns (spoiler: there doesn't seem to be). The ebook is available from Lulu for the cost of production only, also some contributing authors have posted free to download links for the book. Download and read – it won't take that long.

I have voted for this book as a write-in vote for the Goodreads Choice Awards 2013 in both the Non-Fiction and Début Goodreads Author categories. Apparently Goodreads uses the average rating of the book to 'weigh' the validity of write-in votes (presumably as part of their decision to censor those votes - but I digress) so I've also rated the book five stars. I encourage others to do the same (even if you feel the need to re-rate the book after the awards have closed).

I leave the final word to the (former) owner of Goodreads:

"I hope you’ll appreciate that if we just start deleting ratings whenever we feel like it, that we’ve gone down a censorship road that doesn’t take us to a good place." — Otis Y. Chandler, Goodreads CEO

Sometimes it's easy to get distracted reading [a:Agatha Christie|123715|Agatha Christie|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/authors/1321738793p2/123715.jpg]. You get used to the idea that she's the creator of Poirot, of Marple, even of Tommy and Tuppence. Those characters can almost become more important than the novel itself, and when you read a Christie that doesn't have the distraction of a famous detective creation you can be surprised by just how good Christie can be. To be fair, those other novels with Poirot in are pretty good too but this one struck me that I was just enjoying [b:The Man in the Brown Suit|12034587|The Man in the Brown Suit (Colonel Race, #1)|Agatha Christie|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1337094995s/12034587.jpg|995869] on it's own single-novel merits than with say a Poirot where I'm in part enjoying revisiting the characters she's created.

Sometimes it's easy to get distracted reading [a:Agatha Christie|123715|Agatha Christie|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/authors/1321738793p2/123715.jpg]. You get used to the idea that she's the creator of Poirot, of Marple, even of Tommy and Tuppence. Those characters can almost become more important than the novel itself, and when you read a Christie that doesn't have the distraction of a famous detective creation you can be surprised by just how good Christie can be. To be fair, those other novels with Poirot in are pretty good too but this one struck me that I was just enjoying [b:The Man in the Brown Suit|12034587|The Man in the Brown Suit (Colonel Race, #1)|Agatha Christie|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1337094995s/12034587.jpg|995869] on it's own single-novel merits than with say a Poirot where I'm in part enjoying revisiting the characters she's created.Anne Beddingfield is a woman of spirit. When she witnesses a man falling in front of a train on the Underground she suspects there's more to what, at first glance, appears to be just a tragic accident. Before we know it, she's into full-on adventuress mode and booking cruises and train journeys and chasing down various suspects. At various times she suspects pretty much everybody in the cast of course, so we're left none the wiser. You assume Colonel Race is in the clear – in part because Anne suspects him too much but mostly because he goes on to appear in a couple of later Poirots as a supporting character (although, this is Christie, even that doesn't give him a free pass) – and Mrs. Blair who seems to be having far too much fun helping Anne to be the baddy. Anne's narrative is interspersed with extracts from Sir Eustace's diary, which is a clever idea allowing Christie to provide extra information outside of Anne's direct experience.

All the characters – apart from Colonel Race – appear to be exaggerated for comedic effect. Anne is super spunky; Mrs. Blair is the rich widow (although she's still married she spends so much time apart from her husband she may as well be) who wants to adopt Anne; Sir Eustace is a somewhat pervy older bachelor writing his memoirs; the put upon suspect of the police – the titular man in the brown suit – is rugged, handsome and difficult, etc. and so on. They're mostly silly, but not too overdone. Characters get to appear and disappear in various disguises, even changing gender, and everybody is fooled. But it works, like Superman and his glasses. As a final cherry on the top, the novel features a nicely clever bit of unreliable narration which I always enjoy.

Prequel time. Rather than Reacher the wandering loner, [b:The Enemy|3056089|The Enemy (Jack Reacher, #8)|Lee Child|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1328645105s/3056089.jpg|224289] gives us Reacher the army man; Reacher the Major; Reacher the Military Policeman. Long before the events of the previous seven novels (and referred to obliquely in at least one of them) Reacher got involved in something while he was an MP Major and had to take a demotion as a 'punishment'. This is the story of that something.

Prequel time. Rather than Reacher the wandering loner, [b:The Enemy|3056089|The Enemy (Jack Reacher, #8)|Lee Child|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1328645105s/3056089.jpg|224289] gives us Reacher the army man; Reacher the Major; Reacher the Military Policeman. Long before the events of the previous seven novels (and referred to obliquely in at least one of them) Reacher got involved in something while he was an MP Major and had to take a demotion as a 'punishment'. This is the story of that something.Reacher has been transferred back from Panama to a nowhere base in North Carolina. His transfer papers signed by General Leon Garber (another name from a few of the previous novels). Before Reacher can speak to Garber about that though he's transferred out to Korea himself. In fact Reacher isn't the only investigator MP that's been brought back from Panama and left effectively unattended as he discovers. More complex than your usual [a:Lee Child|5091|Lee Child|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/authors/1377708686p2/5091.jpg] novel, there are multiple stories going on that all, eventually, tie together – more of less. The political story of who authorised the transfers, the secret meeting agenda (there's always a written agenda) is one story. The death of the General Kramer and the murder of his wife on the same day (that seems like too much of a coincidence) is the second story and the first case that Reacher finds on his plate. The murders of the two special forces guys is a third thread (and the second case). And finally, we get to find out a lot of Reacher's family history in the fourth story about the terminal illness of his mother who lives in Paris. All in all a lot to keep track of, but it's handled well. There are a few 'yeah right' moments that are obviously in there to expedite the story, but the pace lets you forgive them mostly.

I was left not quite sure who the titular Enemy was supposed to be though. The murderer(s) that he's tracking down seems too obvious. The political shenanigans that goes on within the military that treats careers as more important than soldiers lives and tries to stop Reacher 'doing the right thing'? The change in the enemies of the US – with the former Soviet cold war situation falling apart – means that Reacher is already starting to think, and talk, about possible redundancy? Or just the old enemy of Death, the shadow over both the Reacher brothers as they worry about their mum?

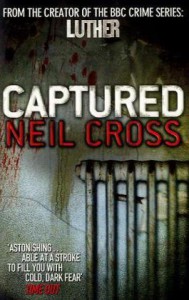

Captured

Because [a:Neil Cross|79765|Neil Cross|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/authors/1314382745p2/79765.jpg] is turning out to be such a slacker in producing the, much anticipated, sequel to [b:Luther|12284181|Luther The Calling|Neil Cross|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1347970358s/12284181.jpg|17132553] (currently holding the unimaginative title of [b:Untitled|17395181|Untitled. by Neil Cross|Neil Cross|/assets/nocover/60x80.png|19109359] and delayed, again, until Spring 2014) I ended up grabbing another one of his books from Louise's bookshelf to fill the wait. [b:Captured|9396394|Captured|Neil Cross|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1348115922s/9396394.jpg|8912503] is the fascinating tale of a rather sad and pathetic protagonist, Kenny, who has been diagnosed with terminal cancer. Instead of telling his ex-wife and friends and living out his remaining days he decides to track down a number of people from his life who he feels he's wronged or mistreated in some way. Sort of like the 8th step of the AA programme meets the My Name is Earl TV show – depending on your personal background. Most of these people are easy to track down and apologise to – although they all seem a little bemused by the experience. Only one, Callie Barton, a girl he knew at school, who was nice to him when nobody else was and he felt he should have shown more gratitude to, has disappeared.

Because [a:Neil Cross|79765|Neil Cross|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/authors/1314382745p2/79765.jpg] is turning out to be such a slacker in producing the, much anticipated, sequel to [b:Luther|12284181|Luther The Calling|Neil Cross|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1347970358s/12284181.jpg|17132553] (currently holding the unimaginative title of [b:Untitled|17395181|Untitled. by Neil Cross|Neil Cross|/assets/nocover/60x80.png|19109359] and delayed, again, until Spring 2014) I ended up grabbing another one of his books from Louise's bookshelf to fill the wait. [b:Captured|9396394|Captured|Neil Cross|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1348115922s/9396394.jpg|8912503] is the fascinating tale of a rather sad and pathetic protagonist, Kenny, who has been diagnosed with terminal cancer. Instead of telling his ex-wife and friends and living out his remaining days he decides to track down a number of people from his life who he feels he's wronged or mistreated in some way. Sort of like the 8th step of the AA programme meets the My Name is Earl TV show – depending on your personal background. Most of these people are easy to track down and apologise to – although they all seem a little bemused by the experience. Only one, Callie Barton, a girl he knew at school, who was nice to him when nobody else was and he felt he should have shown more gratitude to, has disappeared.Cross's background in TV screenplays seems a little too apparent (as with Luther) where his prose is more direct and functional than you might hope for. More of a tell rather than show style. But what he maybe lacks in style and characterisation he surely makes up for in spades with ideas, plot and more twists than you can shake a twisty stick at. The journey of Kenny as he finds out that Callie really is missing, digs up the old police investigation and starts his own investigation and interrogation of Callie's husband, Jonathan, is horrific to follow. As the pathetic cancer patient at the start of the novel transforms into an avenging angel of destruction by the end. Cross is clever and keeps you guessing all the way – what has happened to Callie; what was Jonathan's involvement in her disappearance; and just how far will Kenny go to find out?

Again, this book has the same things I loved and the same things that irritated me with Luther. The blunt prose and the shallow characterisations (like he expects the actors to take up some of that slack) are overshadowed by the clever premise, the unique twists and turns of the story and just the general darkness of Cross's brain of incredible ideas.

Flag in Exile (Honor Harrington, #5)

This fifth book felt like a return to to the promise of the early series for [a:David Weber|10517|David Weber|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/authors/1227584346p2/10517.jpg]. With her lover murdered in the previous novel, and her own exile from Manticore as a direct response to the resulting duel, [b:Flag in Exile|77738|Flag in Exile (Honor Harrington, #5)|David Weber|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1321561696s/77738.jpg|4360] leaves Honor heartbroken and moping about on her steading on Grayson. With the rising of hostilities between Manticore and Haven, it's only a matter of time before the ships protecting Grayson have to be redeployed. Grayson will no doubt need a new leader for their own fledgling navy to take of the slack.

This fifth book felt like a return to to the promise of the early series for [a:David Weber|10517|David Weber|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/authors/1227584346p2/10517.jpg]. With her lover murdered in the previous novel, and her own exile from Manticore as a direct response to the resulting duel, [b:Flag in Exile|77738|Flag in Exile (Honor Harrington, #5)|David Weber|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1321561696s/77738.jpg|4360] leaves Honor heartbroken and moping about on her steading on Grayson. With the rising of hostilities between Manticore and Haven, it's only a matter of time before the ships protecting Grayson have to be redeployed. Grayson will no doubt need a new leader for their own fledgling navy to take of the slack.This novel is the continuation of Honor's Grayson story. The same prejudices are at work as in the previous book. While her own people are behind her, but there are other factions that still see her as a threat to both their religious and their male hegemony. Can she defend the planet from the Havenites, and defend her steading and the political leadership that supports her from an emerging terrorist group? Short answer is no, and that's kinda why it works. Honor can't sort both the 'a' plot and the 'b' plot entirely by herself. She needs help and the two stories sit comfortably alongside each other without feeling like their competing to be the 'a' plot, or overly competing for Honor's attention.

The bad guys still suffer from being a little too shallow – religious and misogynist bigots will do what religious and misogynist bigots do (and pretty much only that). And the supporting good guys are all a little too consistently honourable and upright. Weber isn't big on depth in his supporting characters. Really only Honor herself has any real development or depth lavished upon her. But that doesn't really matter, these are fun military science-fiction stories, and the next one in the series is already added to my to-read list...

The second book in the Louise Recommends challenge – where Louise gets to force a book on me every three months. She said [a:Donna Tartt|8719|Donna Tartt|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/authors/1380323240p2/8719.jpg]'s [b:The Secret History|70897|The Secret History|Donna Tartt|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1327764557s/70897.jpg|221359] was her favourite book – of all time – what if I didn't like it? So determined was she that, having misplaced her own copy, she went out and bought a new one just so I would have no excuse. Reading the sleeve notes it's a novel about a bunch of kids studying classics at university. Sounded pretty dull. I saved it up for a nice long flight to Boston (I hate that the flight attendants get totally overworked about reading a Kindle during take-off and landing, so now I just take at least two big paperbacks with me as well – this trip I took five, but those reviews will hopefully come later) and read pretty much three-quarters of it on that flight. The remaining chapters I raced through in the next two days inbetween exploring beautiful autumnal Boston.

The second book in the Louise Recommends challenge – where Louise gets to force a book on me every three months. She said [a:Donna Tartt|8719|Donna Tartt|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/authors/1380323240p2/8719.jpg]'s [b:The Secret History|70897|The Secret History|Donna Tartt|https://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1327764557s/70897.jpg|221359] was her favourite book – of all time – what if I didn't like it? So determined was she that, having misplaced her own copy, she went out and bought a new one just so I would have no excuse. Reading the sleeve notes it's a novel about a bunch of kids studying classics at university. Sounded pretty dull. I saved it up for a nice long flight to Boston (I hate that the flight attendants get totally overworked about reading a Kindle during take-off and landing, so now I just take at least two big paperbacks with me as well – this trip I took five, but those reviews will hopefully come later) and read pretty much three-quarters of it on that flight. The remaining chapters I raced through in the next two days inbetween exploring beautiful autumnal Boston.Luckily, it's not dull. Far from it. It's not even really that much about kids studying classics. Instead what it actually is, is a tightly crafted murder mystery. Although without much of the mystery – we know that Bunny is going to die pretty much from the first page; and we know that the rest of the group are all party to the murder. But we don't know how it's going to happen and we don't know when. Even more confusingly, Tartt continues to break with agreed murder-mystery traditions by having the murder, that we already know about, take place slap-bang in the middle of the book. Suddenly you're left wondering what the remaining 324 pages are going to be about. But, don't worry, it's all perfectly handled. The two halves of the book are like the two sides of a hill. The first half takes us into the cast, the situation and the build up to the murder – the reasons why the characters believe the murder has to happen – then the second half is the fall-out, the repercussions (and there are always repercussions even if there's no Poirot character to sort the whole mess out with his little grey cells) and the recriminations as the group tries to come to terms with what it's done.

Our narrator is Richard Papen and, while the story revolves entirely around his experiences, he seems somewhat unreliable. He lies quite openly during his story on several occasions, sometimes drawing attention to it in his narration, sometimes just letting us spot the lies for what they are. Obviously that throws the rest of his story into some doubt, and while that's not really a problem, it does potentially add another layer of confusion. Richard is a young lad struggling to find his place at college, when he decides to apply to transfer to Hampden College: a university in Vermont. Here his need to be accepted by peer groups takes on a new life. Or two new lives to more specific. In one he's living the shallow university dream of booze, drugs, girls and hangovers, and not really enjoying it too much. In the other he attaches himself to a very select teaching group of misfit students – Henry, Bunny, Camilla, Charles and Francis – and their teacher Julian Morrow. This is the only group he teaches and his condition is that he is the only teacher they have. An already perfectly formed clique that Richard is desperate to be a part of. Actually, the whole cast of the novel are misfits, from the students, to the teachers, and even further out to the families and parents. There's barely a likeable character in the book. Yet somehow, Tartt manages to make this weird sounding book about a bunch of pretty unlikeable classics nerds who commit a murder of one of their own, and where the murder is clearly explained on page one, and has happened by the middle of the book, totally gripping. I had to put the book down frequently during those two days because I was on holiday and supposed to be out doing stuff, but I didn't want to.